Few sectors of the UK economy have achieved the consistently high levels of international recognition that UK higher education has in recent decades.

Our universities are ever more central to the UK’s economic prosperity as well as its social and cultural life.

The UK’s research and innovation system particularly, but not only, in areas such as bio-medicine is impressively productive, delivering societal benefits at a fraction of the cost of its sister system in the United States.

Similarly, notwithstanding developments in immigration policy, UK universities remain a popular destination for international students despite stiff competition from traditional as well as new international competitors.

But as we approach the announcements of this year’s post-general election Comprehensive Spending Review, the higher education commentariat is right to be worried.

As the government’s wider fiscal strategy comes under political pressure, higher education policy, regulation and financing cannot expect to escape the microscope; policy makers have too few levers to pull given various manifesto spending commitments.

The sustainability of learning and teaching…

All the more reason to revisit the analysis and recommendations in the March 2015 report of the HEFCE/UUK Financial Sustainability Strategy Group (FSSG) on the Sustainability of Learning and Teaching.

Whilst the focus of the report is England, the wider issues raised are equally relevant to the rest of the UK HE system.

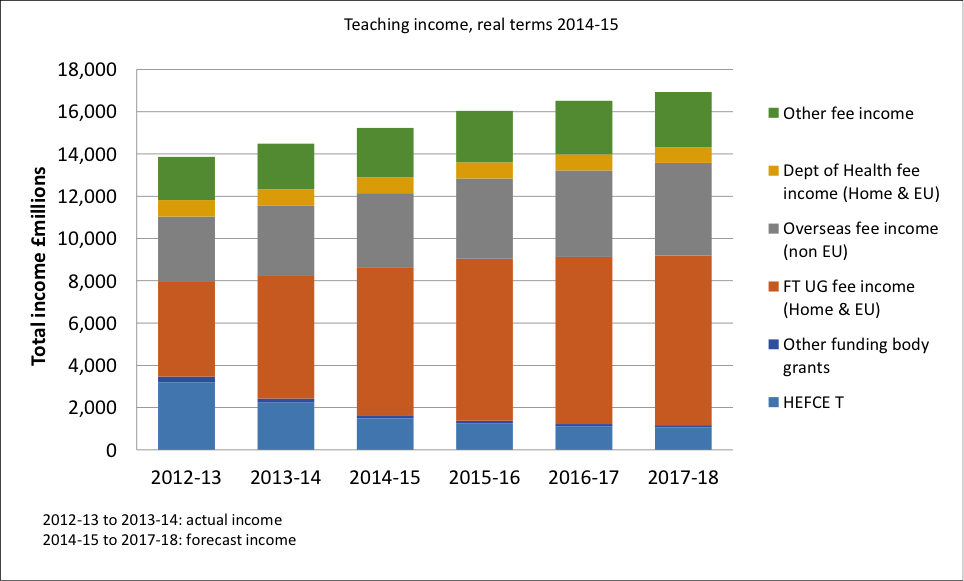

The central argument prosecuted in the report is that whilst institutions have adapted remarkably well to the policy and financing revolution in higher education over the past five years encapsulated in the chart below, there are clear signs that the quality of the system as a whole will suffer in the next five years if some obvious risks are not addressed.

But the issues are complex and addressing them effectively requires a deft touch. It is not simply a matter of pumping more money into the system. It is also about intelligent regulation of a system which requires regulatory certainty in the face of greater levels of market volatility.

For example, the total recurrent resource available for teaching has increased in recent years, notwithstanding increases in student numbers. This does not, however, take account of the big decreases in capital funding.

A much greater proportion of institutional income is now derived more directly from student recruitment in the form of tuition fees. Income therefore fluctuates from year to year due to market factors outside their direct control. As some institutions have expanded student numbers others have contracted with a consequential loss of income.

So despite all of the talk of success, institutional resilience, self-reliance, chances are that most of us are beginning to feel the pinch. That is, unless you’re among the very few which have big reserves, growing endowments or have the wherewithal and change management capability to re-engineer your institutional operating model, chances are cash is becoming increasingly scarce.

And yet this shift in the university/state relationship is under-appreciated by government and poorly understood by the public, for this shift has been nothing short of seismic.

For these and related reasons the FSSG’s report says there are eight major risks to the future sustainability of institutions.

Real and present risks to future sustainability….

Risk 1. Costs of operating in the new market environment are rising, and there is limited scope to control this. Likelihood: certain. Impact on sustainability: high.

Real, competition-related costs such as marketing, borrowing costs and IT investment to improve student administration for example, are all real operating costs, but are often seen by students and campaigners as diverting resources from direct student support.

Risk 2. The core source of university income is at a level capped by government (home/EU student fees) and is declining in real terms. Likelihood: very high. Impact on sustainability: increasing rapidly.

The sector is seeing its main teaching income – tuition fees — declining in real terms year on year while costs increase.

Risk 3. Failure to generate enough cash to support increased investment and higher operating costs in the new competitive student market. Likelihood: high. impact on financial sustainability: significant for some.

This manifests as a threat to improving productive capacity especially to investment in physical and virtual infrastructure, new teaching and learning methodologies, and efficiency gains in administration. Nearly all institutions are planning to increase cash generation, not all will succeed.

Risk 4. Income is more volatile and uncertain. Likelihood: certain. impact on sustainability: significant for some.

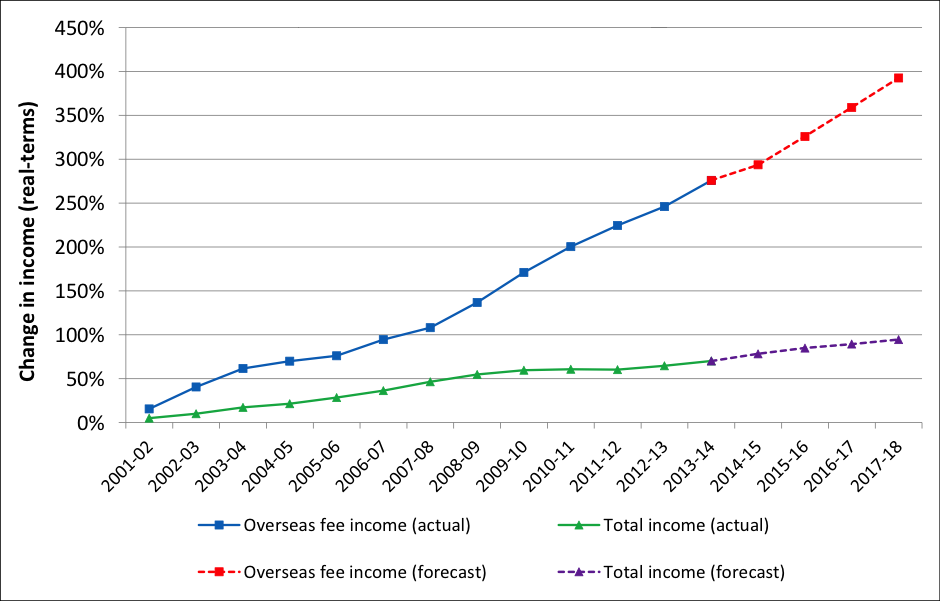

Any decline in student numbers due to demography, events in international markets or further tightening of visa/immigration policy will directly reduce income. As the chart below demonstrates, all institutions are banking on year on year increases in international student numbers to solve the problem!

Risk 5. Further possible changes in the new environment could create a downside risk. Likelihood: very likely that one or more of these will manifest. impact on sustainability: significant.

A number of aspects could cause concern, but the most obvious are:

- Any decision to review the funding/fees settlement established in 2012.

- The possibility that policy further encourages alternative providers with these becoming much more significant in the mainstream undergraduate market.

- Threats to the international student market – either from actions overseas, or from loss of reputation resulting from policy factors (e.g. Immigration controls/enforcement)

Risk 6. Pensions liabilities – different for different institutions but significant for the sector. Likelihood: certain. Impact on sustainability: potentially high.

There is a short-term issue about the additional costs of paying more into schemes, some of which will continue to be in deficit. A second issue is that as pensions deficits have to be shown in financial statements this may impact on the perceived or actual credit–worthiness of universities, thus adding to borrowing costs. Thirdly, there is a longer term demographic issue of there being fewer people working to support a larger number of pensioners. The result of these factors is that all institutions (and employees) are going to have to spend more to avoid a pensions’ crisis in the years to come.

Risk 7. The workforce does not receive the leadership and support it will need to adapt to the challenges of the new environment, including further improvement of the student experience. Likelihood: certain. Impact on sustainability: potentially high.

The staffing practices that have served universities in the past are likely to need to change, and probably to do more rapidly than in the past. The risk is that university leaders and governing bodies underestimate the critical importance of this area, and do not provide the quality of leadership, and the level of support that staff will need.

Risk 8. Failure to compete effectively with universities in countries which are investing much more in their HE systems. Likelihood: medium. Impact on sustainability: significant for some.

Graduates from our universities need to be equipped with the skills and experience to compete and succeed in global markets, whether this is in Sydney, Shanghai, Lima or London. This means that for many (although not all) institutions, success and sustainability mean investing and innovating enough to keep pace with their peer universities overseas.

To conclude…

Despite the fact that our institutions are extraordinarily well-managed and have proven to be adaptable in the face of the big policy shifts of recent years, the situation is pretty fragile. Expectations on the system are rising, but so are operating costs. People-related costs are high and increasing due to pensions and a host of other challenges, but income volatility is manifesting at a rapid rate. Increased cash generation lies at the heart of all institutions’ financial strategies, but as the chart above on overseas income shows, all institutions are relying on similar measures to ameliorate the challenge. Some will succeed, other will not.

The UK has been a world leader in HE, but this dominance is slipping and will slip further with poor policy and financing choices. Let’s hope that the forthcoming CSR does not lead us down this path.