Looking In After Stepping Out: A Global Perspective

Ian Creagh spent 20 years working in higher education leadership, most recently as Chief Operating Officer at King's College London. He left this role last year, and now has a portfolio of roles within the higher education sector. Here he considers current challenges for the sector from an international perspective, and identifies issues that are common across the globe.

After 20 years as a head of administration in three universities in two countries, last year I resigned from the post I’d held for 10 years at King’s. My motivation? Simple really. I’d decided it was time to learn some new ways of working and earn my income in a different way. One that was more varied, involved more personal choice and was more hands-on than working life over the previous 20 years, fulfilling as those years had been.

I’ve gone plural and now earn a living from a portfolio of roles, all of which, to varying degrees, still involve higher education. I can recommend it.

One of the more pleasant aspects of working life over the past six months has been travel to my country of origin, Australia, a couple of times, as well the US, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Flanders and the Walloon region of Belgium, and Sweden.

Interesting as each individual assignment has been, of even greater interest has been the opportunity to observe and reflect on some of the broad brush strokes painted across the global higher education canvas.

Despite the myriad of differences in funding and financing, the degree of marketisation and the particularities of the local political and policy context, it is striking how similar HE leaders’ perceptions are of the big challenges impacting on HE globally.

The received operating model. Are we nearing a point of discontinuity?

Whilst universities may exemplify Steven Johnson’s observation that our great social, economic and cultural institutions are the giant redwood trees of modern civic life, having adapted and evolved almost in spite of the ebb and flow of policy fashions, the future feels much less certain.

The underlying operating model that provided the platform for the historic shift from elite to mass higher education in the post-World War Two era and the rise of the research university – a predominately face-to-face, didactic teaching model, a permissive approach to who gets to do research with weak controls on volumes, and a high tolerance for fragmented service provision — remains eerily dominant 70 years on.

But that model now feels under threat in a reasonable proportion of the higher education world. Universities have become immensely expensive places to run. Their internal economies are fuelled by sophisticated forms of cross-subsidisation which are poorly understood by most stakeholders, not least students who, in countries like England, Australia and the US, now provide universities with a large proportion of their revenue.

My observation has been that the issues listed below, in no particular order of priority, seem to weigh on the minds of institutional and sectoral leaders across the globe:

- HE policy-makers are being buffeted by all sorts of headwinds and challenges which are categorically different in their complexity to those in the recent past. They’re all dusting off their PESTLE analyses because the old ones feel out of date

- As with everything, the challenges are increasingly global in both character and dimension, requiring forms of collaboration which HE sectors and institutions often find it difficult to reconcile with perceptions of their enduring mission

- The historic geopolitical shift eastwards – to China, India and beyond – but what to do about it in terms of practical strategic adjustment?

- The insatiable thirst for innovation characterised by the advent of robotics, artificial intelligence and big data. Everyone agrees universities have to be part of it, but how?

- Knowledge-production is no longer monopolised just by universities alone – this space has become contested, as has credentialing of teaching programmes by for-profit institutions competing directly for students, and

- The decline of deference for institutional tradition and the rise of a generation wanting to challenge the traditional psychological contract between institutions and students.

But if the above list forms the basis of universities’ governing body and senior leadership retreats, two more immediate issues seem to be dominating senior teams’ attention across the globe, both of which stem from the received operating model coming under increasing pressure.

Dilemma number one: how to make the economics work…

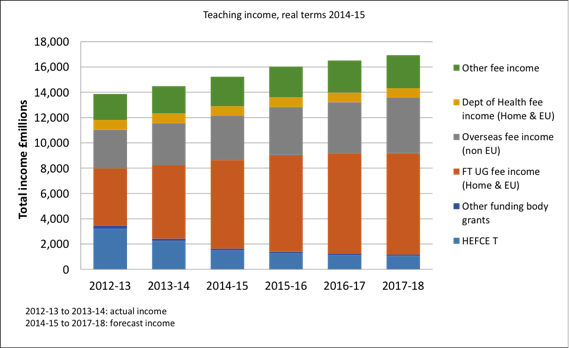

Despite the significant increases in student tuition fees here as elsewhere, funding for HE teaching has been sharply reduced, with the proportion of teaching income in England’s universities derived from HEFCE teaching grants falling from 66% in 2011-12 to just 17% in 2015-16. Most of the residual teaching grant is now focused on high-cost, strategically important STEM and clinical courses.

The same longer term trends are evident in Australia and the United States. In England, shifts in revenue funding have been accompanied by equally significant changes in the allocation of capital grants. These have declined by 85% between 2009-10 and 2012-13 from a level of funding that was relatively modest, not least because of the capital funding backlogs associated with the 1990s.

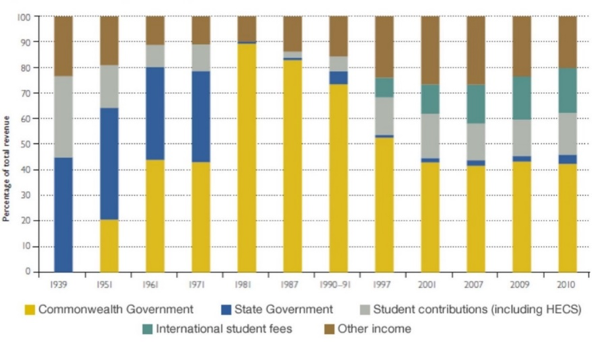

Source: Commonwealth departments of Employment, Education and Training; and Employment, Education and Workplace Relations

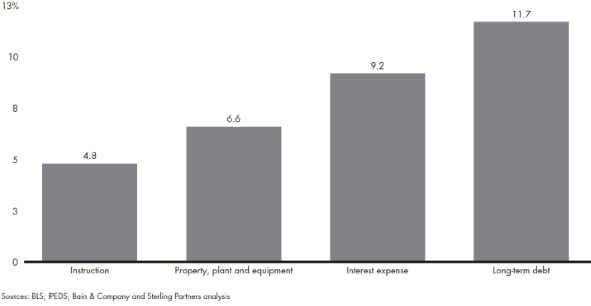

These events have led to two related developments: a significant increase in institutional debt; and a desire to improve significantly the operating performance – financial and otherwise – of institutions on the assumption that this will provide the underpinning foundation of their ability to raise debt to finance capital investments in teaching, research, IT and student facilities.

Source: Bain & Co, Sterling Partners

Universities UK noted that while in 2009–10 only around 11% of capital expenditure was financed from internal cash, this was projected to rise to around 75% by 2017-18, having hit 31% in 2014/15. Borrowing is the second largest source of funding for capital investment.

In generating the necessary margins required for optimal levels of long-term capital investment, everyone seems to be struggling with the challenge of getting a tighter grip on their fixed costs and thinking differently about estates/academic space strategy, without losing the support of academic staff.

Dilemma number two: wrestling with depth verses breadth in a HE market economy….

It is understandable that university leaders want to preserve longstanding discipline-based departments and degrees that are woven into the fabric of their university’s life. And the vagaries of changes in undergraduate student demand definitely argue for more prudent strategy-led action and less knee-jerk tactical manoeuvring for short-lived gains.

But increasingly, university leaders in all but the most financially secure institutions across the globe are questioning if in the long-term they can sustainably operate with big differences in the relative margins contributed by different faculties. The apparently inescapable, pronounced shift over the past 15-20 years towards market-based higher education has exacerbated this challenge.

Here, as elsewhere but particularly in Australia and the US, escalating tuition fees, greater student choice, new for-profit providers, uncapped student places and the increased policy emphasis on teaching performance mean universities have to think far more critically about the breadth of provision.

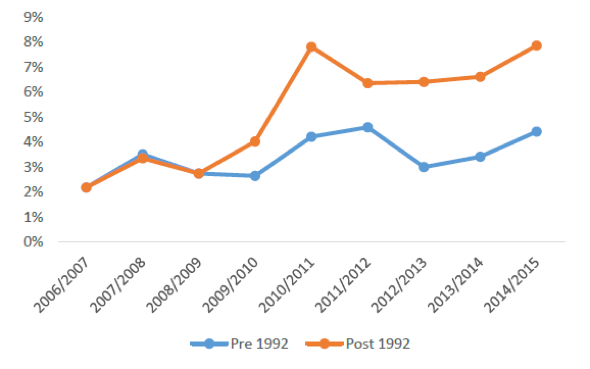

income, UK, pre- and post-1992 institutions

Source: KPMG benchmarking 2016

Many heads of administration and finance directors will be all too familiar with the sensitivities and intricacies of cross-subsidisation within institutions whereby income derived from educating students in one area provides the financial ballast for very high-cost subjects in another as well as contributing to a university’s overhead costs with respect to research.

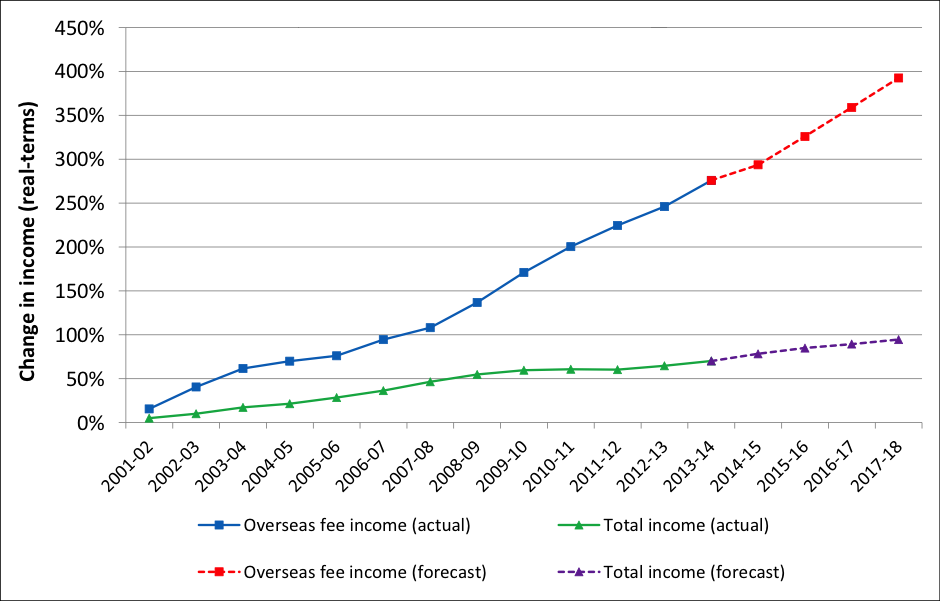

While universities typically have a pragmatic rapport with funders and policymakers, explaining how their internal economies work to students and the wider public is another matter altogether. More immediately, our collective experience of relying on international student recruitment as a means of papering over these challenges must surely be under threat for some institutions at least. It stands to reason that there will be as many institutions that underperform against their forecasts as those who achieve their objectives. Everyone seems to agree that our — ie. all counties that actively recruit large numbers of fee paying international students — collective reliance on this revenue stream constitutes a significant financial risk. Immigration policy changes as they relate to international students make this risk more acute in the UK.

Another dimension of the breath verses depth dilemma is the funding of research overheads. The arguments surrounding FEC are well rehearsed in this country. Whilst this phenomenon has featured in most conversations I’ve had in several countries over the past six months, my crude assessment is that we sit somewhere between the US and Australia. The United States remains something of an exception, as US funders tend to be more comprehensive in terms of overhead funding.

Australia’s most research intensive institutions on the other hand, lacking the safety belt of a dual support research funding system, will typically educate much larger numbers of students than in their UK equivalents, resulting in much higher student to staff ratios, typically in excess of 20:1.

Optimism about the future

Yet despite the scale of these challenges, heads of administration and other university leaders in all of the places I’ve visited remain incredibly optimistic about the future. Many are running wide ranging transformation programmes to grip current and future challenges; and it’s wonderful to observe the extraordinary professional services talent that universities are growing as well as attracting from other sectors.

Partially in response to this, I’m currently working with the Heads of University Management and Administration in Europe, HUMANE, to deliver some very high quality development programmes for professional staff. Building on the success of the well-known Barcelona Winter School, this year we’ll deliver a Berlin Summer School and a Hong Kong Asia-Pacific School. I commend these programmes to you and more information is available on the HUMANE web site.

Greetings from the outside!