Office of the Independent Adjudicator: Who’s Complaining and Why?

With student complaints rising, Karen Stephenson, University Secretary, Birmingham City University, breaks down the latest findings from OIA.

Student complaints are at a record high. The latest available OIA Annual Report shows that there were 2,850 complaints, an increase of 3% from the previous year. ‘Complaints closed’ or processed to a conclusion were up by 6% to 2,821. The annual increase in complaints has been ongoing since 2017 and is perhaps a reflection of the changing attitudes of students towards their universities. An expectation of ‘service’ in exchange for money appears to be impacting students’ propensity to lodge formal complaints.

Who’s complaining?

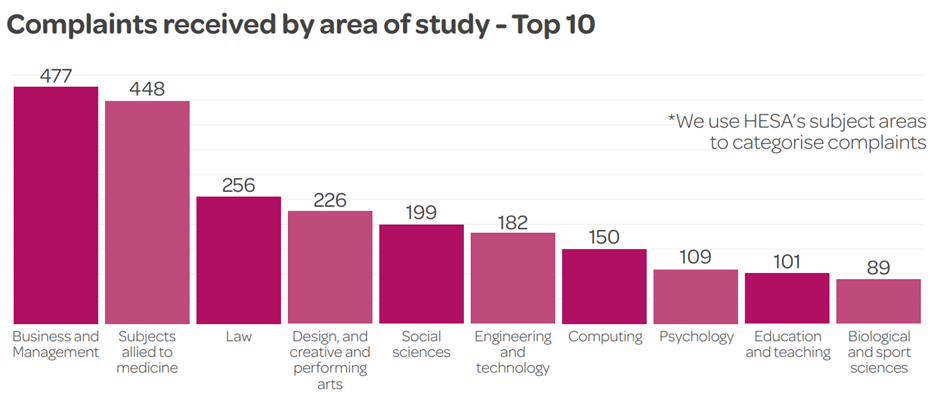

The least complaints arise from those studying languages, education / teaching and engineering whilst the largest number arise from students of business programmes. This may be a result of the large numbers of students studying business subjects.

Nearly two thirds of complaints (65%) are made by home students while over a quarter (27%) are made by international students and 7% by EU students. Interestingly international students (non-EU) are disproportionately represented, 19% of students but 27% of student complaints.

The majority of complaints are made by undergraduate students (57%) but those following post graduate and PhD programmes are disproportionately represented. This latter group constitutes 28% of the student population in England and Wales but accounted for 35% of all complaints.

Themes of Complaints

In 2021 complaints which related to teaching supervision, facilities which impact the course or disruption arising from the effect of Covid-19 and industrial action constituted 45% of all complaints. Service disruption as a result of both Covid-19 and industrial action was unquestionably a challenge. Some courses failed to mitigate for missing content and there were examples of alternative arrangements not being accessible to all students. However individual complaints associated with Covid-19 were often rooted in issues which related to the practical aspect of learning programmes. This included access to laboratories, cancelled or changed projects and placements which did not take place. In addition, those on design and creative / performing arts courses were similarly negatively impacted. Service issue complaints declined as a percentage of all complaints in 2022, down to 38%. This remains a large number and is the joint largest percentage of complaints with academic appeals. The reduction in service issue complaints is attributed to fewer Covid-19 related complaints than in 2021.

In 2021 complaints associated with academic appeals constituted 29% of all complaints. In the 2022 report this rose to 38%. The increase in academic appeals complaints is likely to be a reflection of the end of ‘no detriment’ or ‘safety net’ policies which were introduced during the pandemic. These policies resulted in fewer appeals and fewer complaints. A range of other issues account for relatively small proportions of complaints within different themes: financial 6%, welfare – non-course service issues 4%, disciplinary issues 3%, equality law / human rights 4%, disciplinary matters – non-academic 3% and fitness to practice 2%.

Outcomes

The OIA concluded / closed 69% of complaints within six months of receipt. This fell short of its target of 75%.

A quarter (25%) of all complaints were deemed to be: justified 3%, partly justified 7% or settled in favour of the students 15%. Three quarters were considered not justified, were withdrawn or deemed not eligible.

There appears to be a communication issue with students and those advising them. This seems to be associated with what the OIA can do and cannot do. Also a principal reason for the designation of ‘not eligible’ (21%) to complaints is that students did not obtain a Completion of Procedures letter from their institutions. They did not pursue and complete their universities’ internal complaints procedure. In addition, 11% of complaints with a not justified outcome had received an offer from the provider in an attempt to remedy the issue. The student had chosen not to accept this offer. The OIA agreed that the complaint had merit but considered the provider’s offer reasonable. In consequence the complaint was not upheld.

Putting things right

The OIA’s approach to complaints which they have deemed to be justified or partly justified is to make recommendations. This was done in 270 cases during 2022. The aim was to “put things right” [1]for the student or students involved. In addition the OIA suggests improvements to procedures or processes within HEIs where this is appropriate. The aspiration is to devise practical remedies which place the student in a position they would have been in if things had not gone wrong. A similar approach is taken with cases that the OIA settles. Examples of settlement agreements that both students and providers agreed to in 2022 included:

· “To uncap a student’s module mark, to recalculate the student’s overall award mark using the uncapped mark, and to reconsider the student’s profile and the new award mark to see if they were eligible for a higher degree classification. This was because we were concerned that the provider had applied its regulations unfairly. The student was subsequently awarded a first class honours degree. Annual Report 2022 30

· To remove a clause in the provider’s pre-existing offer to settle the student’s complaint that tried to prevent the student from speaking about their complaint or taking any further action in relation to any other complaint the student might have about the provider.

· To reconsider whether a student was able to continue with their studies under the provider’s support for study process, and to apologise and pay them compensation for distress caused by not following the process fairly.”[2]

When a complaint is upheld or partly upheld, the OIA seeks a practical solution with a view to putting the student back in the position they would have been in if things had not gone wrong. Example of these practical remedies which were recommended in 2022 include:

· To reconsider the decision not to allow a disabled student to step away from their studies for a period (as well as to pay the student some compensation). This was because the provider didn’t properly consider the knock-on impact of a lack of support in the student’s first year on their progress in the second year, or think about whether additional support might be needed when their mental health deteriorated.

· To remove a cap on resit marks because the provider had not fairly applied its policy to adjust the assessment regulations for students affected by the disruption caused by Covid-19.

· To rehear a case of suspected academic misconduct against a student as the original process had not been fair.

· To send a student an outcome to their complaint about a member of staff, setting out what the provider had decided the facts of the case were, whether it had decided that the behaviour in question would reasonably leave someone distressed, whether it had identified any changes it could make to improve its processes or policies, and whether it identified anything further it should do to support the student who made the complaint.

· To give a student information about external funding obtained by the provider for their project, and what had happened to the funding, so that the student could make an informed decision about whether to bring their complaint to the attention of the funding body.[3]

· To send the student course materials that they had not been able to access online as they were studying from prison.

If a practical resolution was not possible, or was not considered to be sufficient, the OIA recommended financial compensation. Examples of this include:

· To refund one year’s tuition fees to a nursing student and to offer to reconsider fitness to practise concerns because there had been a significant delay in dealing with the student’s disclosure of a criminal conviction before they started the course, and the self-disclosure was not considered during their appeal

· To refund a proportion of tuition fees to a group of students and to pay compensation for the severe disappointment, distress and inconvenience caused by significant and ongoing issues with the delivery of their course and the impact of this on them, and for not investigating their complaint properly

· To refund fines that a student had been told to pay following an unfair disciplinary process, and to pay the student compensation for distress and inconvenience.

· To pay for costs incurred by a student as a direct consequence of an administrative error by the provider that led to them paying placement and visa fees that were wasted.[4]

Conclusion

Formal student complaints, Completion of Procedures Letters (COP), the pursuit of complaints beyond the universities where they have arisen has become an embedded aspect of the Higher Education environment. It appears to be accepted that this activity will continue and grow. The OIA operating plan for 2023 states that “we continue to respond to the sustained year on year increases in our case receipts and prepare for possible further rises.”[5] If a ‘silver lining’ can be found in this situation it probably lies in recognising that the institution of the OIA mitigates against widespread litigation which would benefit neither students nor HEIs. During 2022 there were only four legal challenges to OIA decisions.

[1] Annual Report 2022, OIA, page 29 (www.oiahe.org.uk/media/2832/oia-annual-report-2022.pdf)

[2] Annual Report 2022, OIA, page 29-30 (www.oiahe.org.uk/media/2832/oia-annual-report-2022.pdf

[3] Annual Report 2022, OIA, page 30 (www.oiahe.org.uk/media/2832/oia-annual-report-2022.pdf

[4] Annual Report 2022, OIA, page 30 (www.oiahe.org.uk/media/2832/oia-annual-report-2022.pdf)

[5] Operating Plan for 2023, OIA, page 1 (https://www.oiahe.org.uk/media/2779/operating-plan-2023.pdf)

Related Blogs