Unlocking our thinking about space

The COVID-19 pandemic has challenged our thinking about how we teach, work and learn in ways we never imagined. Richard Calvert, Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Strategy and Operations) at Sheffield Hallam University, reflects on the opportunities this creates to re-think campus design and use, and on how we could use campus spaces more efficiently.

I talked in my opening blog about positioning efficiency as a means of enabling strategic value, rather than simply a tool of cost-cutting.

That positioning is particularly relevant as we work through the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the design and use of our campuses, and on our attitudes to when, where and how we work. With that in mind, I’ve focused this blog on some of the issues and choices around our relationship with our university spaces.

This matters from an efficiency perspective because, for most of us, space is the second biggest cost-driver after staff.

But it’s also a strategic differentiator for many of our students and staff, and an enabler of what we do, both in terms of specialist provision, and wider facilities and services.

Like many universities, at Sheffield Hallam we’ve been testing new ways of thinking about space. And we see this as a leadership issue across the academic and professional community, rather than simply one for the estates team.

I don’t think any of us has all the answers on how this will play out, either within the sector or more broadly.

But I’ll share some of the ways we’ve been exploring the issues.

We started with three questions.

First, what are we using space for?

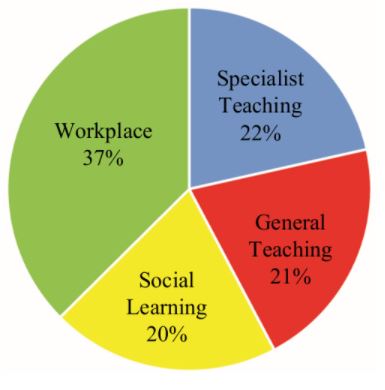

This proved to be a harder question than we might have thought, and not an issue we’d really reflected on. The categorisation we’ve used breaks our space down into four main types, as in the following chart.

Whether or not this is “right”, or why exactly we have this breakdown, is less important than the fact that it enables us to ask some questions and model some different approaches.

That said, two fairly clear conclusions stood out:

- Much of our space is essentially limited to a single purpose, and is often closed off to those who don’t “own” the space

- The balance of non-teaching space is quite heavily tipped towards staff rather than students. This is not surprising given pre-pandemic approaches to the workplace.

Second, how efficiently do we use space?

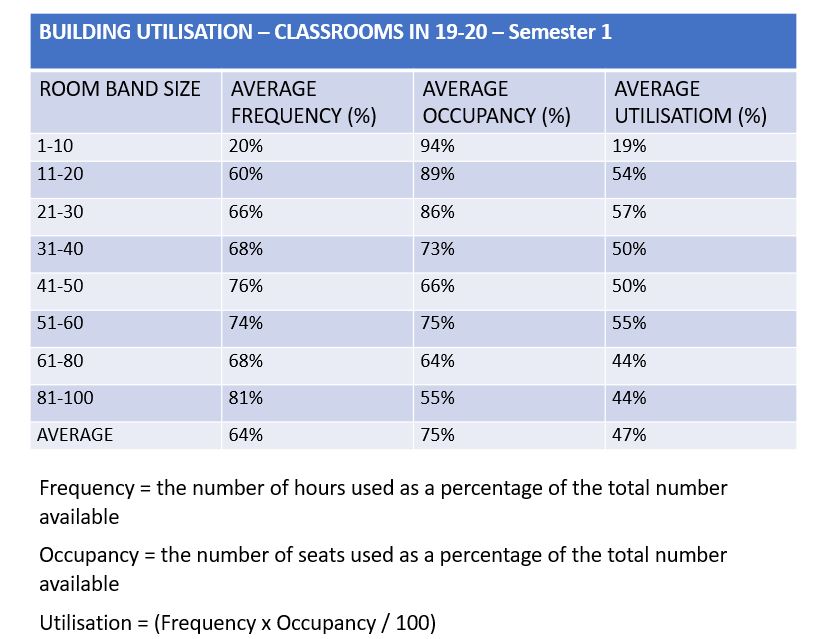

We can model efficiency of use of teaching spaces quite well through timetabling and other data. This paints the following picture:

While probably familiar to many of us, this confirms that much of our teaching space is under-utilised, and that room sizes or configurations often don’t meet requirements.

And although we don’t have such comprehensive data on workspaces, it’s clear that the usage of these spaces is also uneven.

Third, what is our space costing us?

We’re probably all quite familiar with estate spend being a large number in our budgets.

But we’ve done further work to better understand the relative operating costs of different buildings. We have also mapped out the long-term maintenance and refurbishment costs of different parts of the estate.

This has exposed costs which on a 3 to 5 year budgeting model had often appeared hidden.

And it really challenges us to think about what we need from our estate, as well as the trade-offs implicit in our choices.

Where do we go next?

At one level, the answer to those three questions wasn’t unexpected.

I’m sure we’re not alone in acknowledging that we have a large, rather inflexible estate. It has relatively inefficient patterns of usage, and a significant operating cost and long-term maintenance bill.

But it does provide us with a more solid evidence base for where we go next, how we balance the interests and changing expectations of staff, students, and the wider community, and how we deliver financial and environmental sustainability.

Of course, there’s uncertainty about how attitudes and future approaches will evolve. Yet there is an opportunity too – both to shape a different way of thinking about university space, and to address some of the long-standing inefficiencies associated with estate usage and design.

Flexibility, flexibility, flexibility

In thinking about how we take this opportunity, the word we keep coming back to is flexibility.

Greater flexibility is key to unlocking more efficient use of space, and to freeing up some of the costs associated with maintaining under-used capacity.

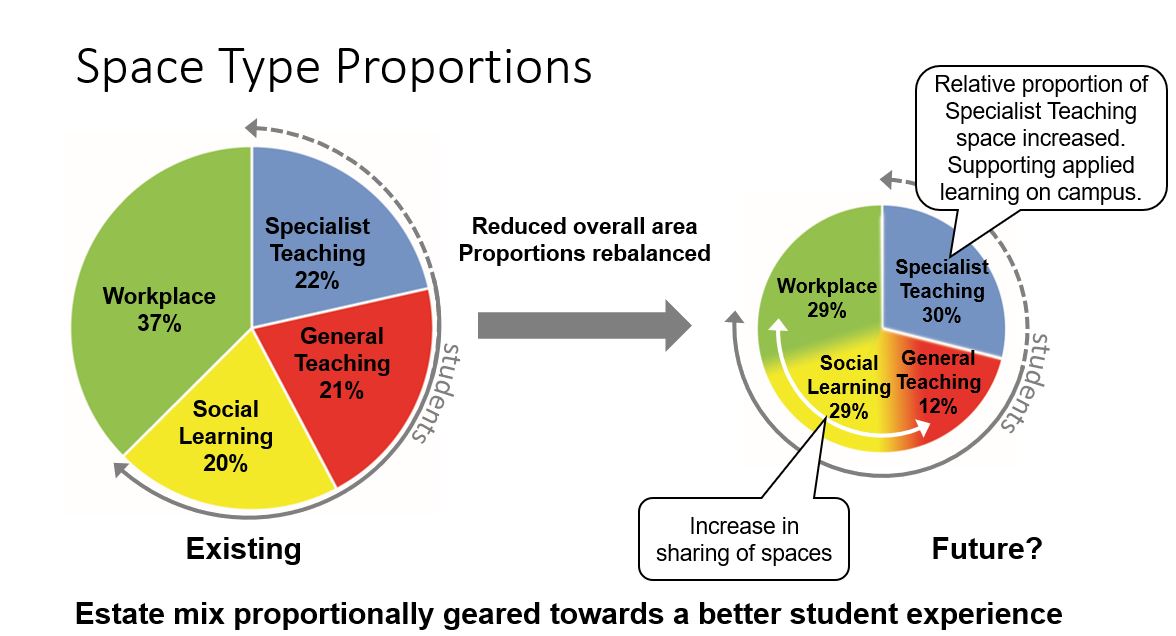

For example, if we could increase the average utilisation of teaching spaces within a normal teaching week from 47% to something nearer 70%, we calculate that we could save upwards of £5m a year in reduced operating and maintenance costs.

That requires greater flexibility in the design of space, but also in approaches to academic delivery. And while this too has changed in unanticipated ways during the pandemic, we now need to work out which of these will be embedded as long-term change, and which will be left behind.

The same goes for workspaces.

We know that many of our staff want to maintain a hybrid pattern of working beyond the current restrictions. But they also want to know that when they come onto campus, they will have good quality and readily available space, suitable storage and other facilities, and a sense of belonging.

Simple hot-desking may be efficient, and may work for some people.

But it’s never going to provide the kind of vibrancy, flexibility, or engagement which is needed across the university community.

Our experience so far is that staff are less concerned about “ownership” of space. But they do want reassurance that appropriate space – including private space where needed – will be available when they need it.

That’s going to require more fundamental changes in the design of space, and in how we cooperate with each other in its use.

A prize worth having

While there are challenges here, there’s much that we can learn from others.

Some of the ways in which we are looking to approach this are as follows:

- Blurring of boundaries across non-specialist categories of space, enabling greater sharing of capacity across staff, students – including research students – and the wider community

- Redesign of non-specialist spaces to offer a wider variety of working, meeting, and learning settings

- Opening up relatively more of our space to students, and making facilities available for wider community use where possible

- Clearer protocols about use of campus space, and expectations around on-campus/off-campus work patterns

- Working with academic teams on longer-term delivery models for teaching and learning, and on how we plan coherently across our digital and physical infrastructure.

And resulting from this:

- A smaller and greener overall estate, with savings re-invested in quality and flexibility of provision.

This potentially moves the chart above into something which looks more like the following:

Predicting the future is probably harder than ever right now.

But the pandemic has changed our attitudes to work and space, and has led to intense and rapid innovation in academic practice.

This gives us a unique opportunity to address some long-standing inefficiencies. More importantly, it allows us to map out a vision for our campuses which is bolder than any of us would have predicted a couple of years ago.

Seizing that opportunity will require imagination, engagement, and leadership right across the university community. But the prize will be worth having for those that get it right.

Richard Calvert is the Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Strategy and Operations) at Sheffield Hallam University.

Related Blogs