Learning to lead in a hybrid world

As we emerge from a world of lockdowns and remote working, many of us see the future as “hybrid”. But what does this really mean, and what are its implications for staff, students and the wider community?

Richard Calvert, Deputy Vice-Chancellor at Sheffield Hallam University, reflects on the opportunities to re-think how we work, but also the challenges for individuals and for leadership.

When a senior Whitehall official recently claimed greater use of her Peloton as an attraction of continued home working, she earned herself a gentle rebuke from her political bosses.

Playing out the home vs office argument in the world of Whitehall is perhaps a little too tempting for politicians and the media, particularly during Party Conference week. But underneath this lies an issue which is increasingly challenging for all of us, both as employers and as individuals.

The impact of hybrid working on campus

In my last blog, I talked about the case for a more flexible campus, seeking ways to break down barriers between spaces and enabling greater shared use by both students and staff. And as students have returned in increasing numbers, we are starting to see a return to something that feels more familiar, particularly from a student perspective.

But the picture for staff remains in many ways more complex. As institutions, it’s often proving easier to buy into the principle of hybrid working than to understand what this really means for how we want our teams to work, and how we get the incentives right to support this.

The transition to hybrid working is of course significantly dependent on what you are transitioning from. While many of us moved overnight from campus to home-working, we shouldn’t forget that many of our colleagues – often in lower paid or more junior roles – continued to keep the infrastructure of the university working throughout the period of lockdown and beyond.

And for others, the experience of home working has been a long way from the apparently calm and curated zoom backdrop by which many of us have come to recognise our colleagues. Instead, it has only compounded challenges, with insufficient or unsuitable home-working space, added pressures of caring responsibilities, home schooling and many more besides.

Despite all this, a hybrid model of working is a clearly preferred pattern of work for many going forward. But do we really know what the “new normal” looks like? Do we know what it means for the future campus experience? And what it means for us as leaders and managers?

The value of creating a workplace community and student experience

This started as a series of blogs on efficiency, and it’s only fair to acknowledge the productivity gains often associated with remote working. For many years I travelled, like millions of others, through an over-crowded public transport system only then to hunt out a quiet place away from colleagues to get my head down and work. With hindsight, I wonder how much more productive it would have been to work remotely on those tasks which don’t require face-to-face engagement.

It can be tempting to think about hybrid working primarily through this “time” axis. Many of the perceived benefits of “hybrid” from an individual perspective are linked to the opportunity to better balance work time with other personal commitments or priorities. And designing our campuses around 50% staff attendance rather than 80% attendance is a very different exercise.

But if we just view this as an exercise in time management, we risk slipping into a kind of “hybrid-lite” which misses the real value of combining both face-to-face and remote working.

This “value” axis goes much more directly to the experience we want to create, both for students and staff, and to our civic mission.

Universities are, and always have been, much more than a place to work. They provide community, wider experience, and are often at the heart of their towns and cities – delivering wider civic benefit and presence. They are also about creating an environment in which we are all able to keep learning and developing.

If we view hybrid working too narrowly, we risk compromising this wider experience and role, and leaving staff either confused about expectations and incentives, or unsure about the experience which they’ll find when they are on campus.

Implementing flexible working on campus

So how do we give staff the flexibility to combine home and campus-based working in a way that works for them, but also ensure that time on campus is demonstrably valuable, to the individual and the organisation? If the value proposition is clear, including in relation to equality, diversity and inclusion, it will become easier to understand how to create the right incentives for staff, and to ensure that the benefits are felt not just by the university and its students, but also the wider community.

I’d offer four reflections:

One

It’s important to set out a vision for the kind of campus experience we are trying to create – what this means for different groups of staff, for our students, and for the places where we are located. Many of us have talked about “hybrid” as the answer, , but in reality it only opens up a further series of questions and choices.

Choices around academic delivery are clearly critical, but so are questions about how students and staff access and experience services, and about the shape and vibrancy of campus facilities and local links.

For those in student-facing roles, this may be about intentional use of different channels to enhance in-person time. More broadly, there is an opportunity to redefine the value of on-campus attendance, with a stronger and more explicit focus on collaboration, coaching, team-working, social engagement and creative activities.

Two

We need to set up our facilities and infrastructure in a way which makes the vision feel authentic. If we’re looking to put a premium on collaborative work, then traditional desking environments don’t provide much incentive.

We need to focus on providing spaces suited to the task and activity, including social and wider learning spaces, rather than focusing on generic or individually-owned spaces. And we need to integrate technology which actively enables and encourages a more hybrid world.

Three

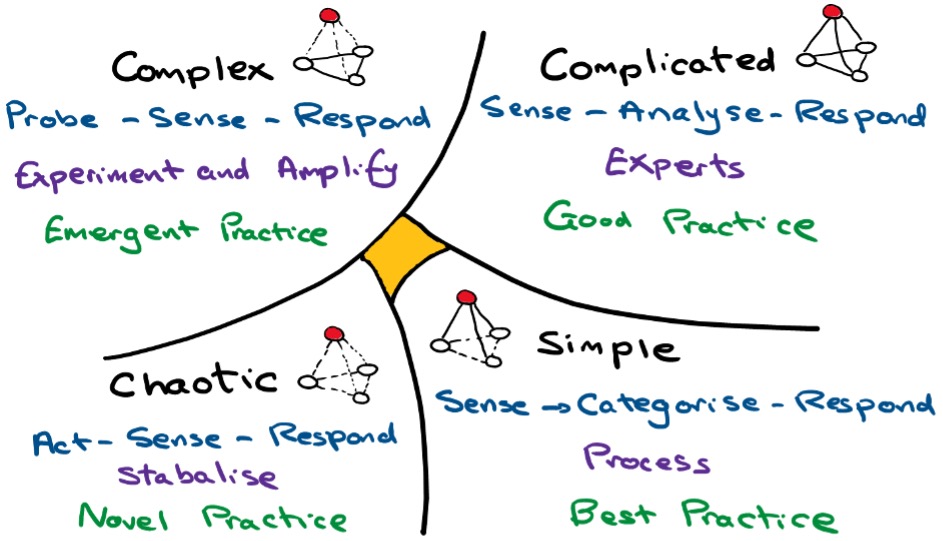

We need to recognise that a hybrid world makes new demands of our leaders as well as our staff. The emerging idea of “hybridity competence” requires us to pivot between worlds in which information is managed, shared and communicated differently; and although as leaders we may now be competent in doing both separately, we have relatively little experience of a world where both happen simultaneously within our teams.

This means that we need to give line managers support on how to run a successful hybrid team, but we also need to support individuals to be successful hybrid workers.

This will take time and need conversations at all levels of the organisation. Critically, it means embedding a more trusting and empowering approach to leadership and management, as getting this right will rely much more on individual and contextual judgements than on a raft of new policies.

Four

We need to keep testing, adapting and learning – and trust ourselves and our staff to get things wrong sometimes. The last year 18 months represents perhaps the biggest upheaval in the relationship between individual and workplace that many of us will ever experience. The implications for staff and student satisfaction are enormous, as they also are for recruitment and retention.

We will not get this right first time, and we should be honest about this. But we should be equally open and systematic in listening, learning and adapting as our experience grows.

The prize for getting this right is starting to take shape – for our staff, our students, and our campuses; and it may frame how we live and work for many years to come. But there’s also a risk of being drawn into something more limited – a kind of hybrid-lite rather than hybrid-rich; and something which accentuates inequality, rather than providing the more flexible and personalised model which many are seeking.

Leading through this next phase may be just as big a challenge as leading through the pandemic, and its consequences may turn out to be even more significant.

Related Blogs